CRITICISM

As the slowly unfolds his travel diary along the pilgrimage through which he lives in the search for self, Fabio Masotti takes us through a review of the infinite variants of that sweet and terrible singleness of scene, that architectural, cosmological centre of the body of the universe, of man, insomuchas it is also the centre and the temple of his actual, authentic reality: painting. The heart which Masotti “shows” usi s the centre of the painting space, it is the tabernacle which sanctifies the temple since it is the living body of painting. Art is both body and temple. Just a sit is space and time, scene and season. The heart of the painting is the intimacy of the language which is defined by being present within the specificità of each single piece: because the variants of the single image are also nothing more than allo f the possible images inside the meaning of the single, specific piece.

The world of affection, of sentiment: the incestuous pulsations and the prepathological stammering of the stilnovista lover become a metaphor for the androgynous search (from Trakl to Musil if you want) – without bothering Duchamp - . Masotti softens such possible cerebral indications from ideology and from conceptual archetypal archeology; in order to speak without any illusions about the bodily value of the liquid yet hard imprint of sentiment, of experience, of existance lived within that space, of that temple, of that body which i stime and place and therefore the temple and the body of our body, of our lonliness and painting insomuchas it has come out of our critical-linguistic search.

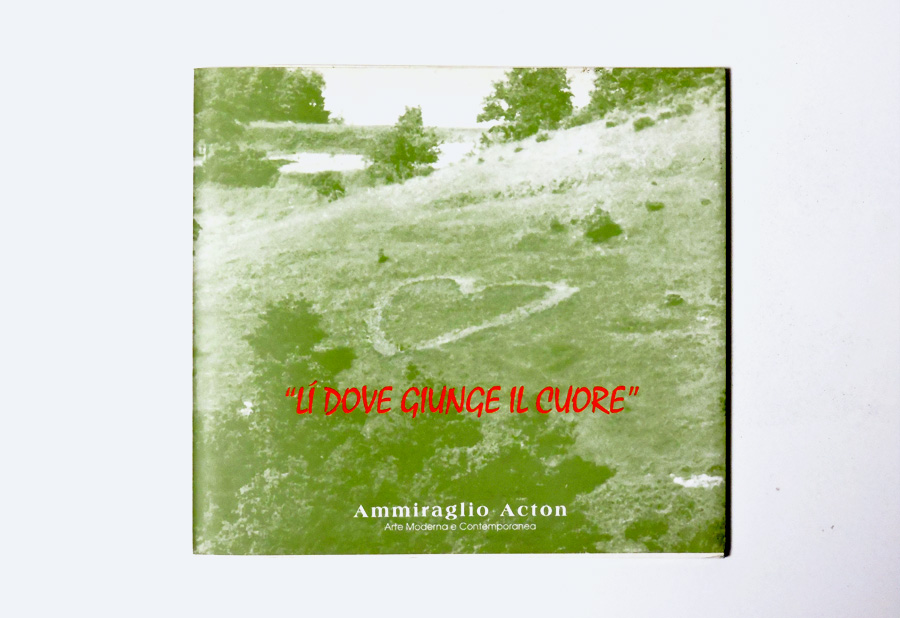

The heart is ridde like a secret in the unploghed field. The farmer knows the Seasons and he farms the rich land: he waters that ridde heart with Energy and makes it beat, so that many other bodies and worlds spring from Mother Earth: and each piece in itself is all of the other possible worlds of other endless pieces. Masotti is the farmer who ploughe his land well, he cuts plate and paper, he glues resin to wax, chalk to tempera and oil sto wood and paper and material and then he bolts and decorates the folds. All this without any definite will to use different materials, without wanting to elevate the use of different materials in praising other “fields”. It i san unrestrained, erotic taking of possession of materials as plurality of variant construction; for its plurality of directions and innovations in composition. The repetition of images eliminates their representative status: it becomes a module, a biologically progressive germination, (an ear to the rabbits of Fibonacci/Mertz, an eye to the gestaltic modulation of the tone of composition, being able to smell the pungenti irony of popularity in the social iconography from the “visual poetry” of “Kisses” to the “Broken Hearts” at school, to the cinematographic pulpings). The singleness of the module declaims the specificità of each work in trying to constitute each work as a finished “icon”.

If intimism is the decorativism of reified sentimentalism, intimacy is the high silence which comes from the depths of sentiment, the purità with which one can remain faithful to the secret of the “Song of Songs”. The intimacy of sentiment, the genuine, existential condition of truth in love, is painting purified from its narrative figuration and raised to the decantation of the image proclaiming itself. Even in the smile – which is somewhere between happiness and selfirony which slowly comes down over the knowledge of the adolescent tragedy of a “finished love”. Those small murders which some suicides turn out to be, are worthy of being listened to by a painting which is a perfect as a prayer full of respect and pity. Love, death and birth. The pilgrimage i san initiation in the knowledge of oneself: the unveiled heart is the centre of the temple of that body of painting which cuts out decorativism and cerebralism, ideologies and superficialità of manner. It i san almost homeless effort if one cannot live the intimacy of sentiment within the plurality of sentiment: strip wood and scratch crystal: will it turn back to look at you? (…)

Masotti softens the corners of the task of “making”: just like two large breasts, the blood pump fills up and the “maternal” figure of the hearts comes out. The module is a “maternal” heart, structured inside the physicality of sweat, of the body which is built in the linguistic manipulation of materials. The heart vibrates in form and colour: and in sound. A heart/gong opens the space for the “representation”. It is the formo f colour, it is the sound of the magnetic field of the series of hearts which pierre the wall. The room becomes a non-clerical nave, the sacred space where the theory of the blood red rosary stands out (after all we are in May) like a Via Crucis made of light and love: “Sacro Cuore” by Joseph Beuys, like in the performance for the Cross (in the auditorium in Aachen in 1964, for the “washing of the feet” in Dusseldorf 1971) or for his poetical intervention in the “santino” of the “SACRO CUORE”: “Der Erfinder der Dampfmachine” 1971.

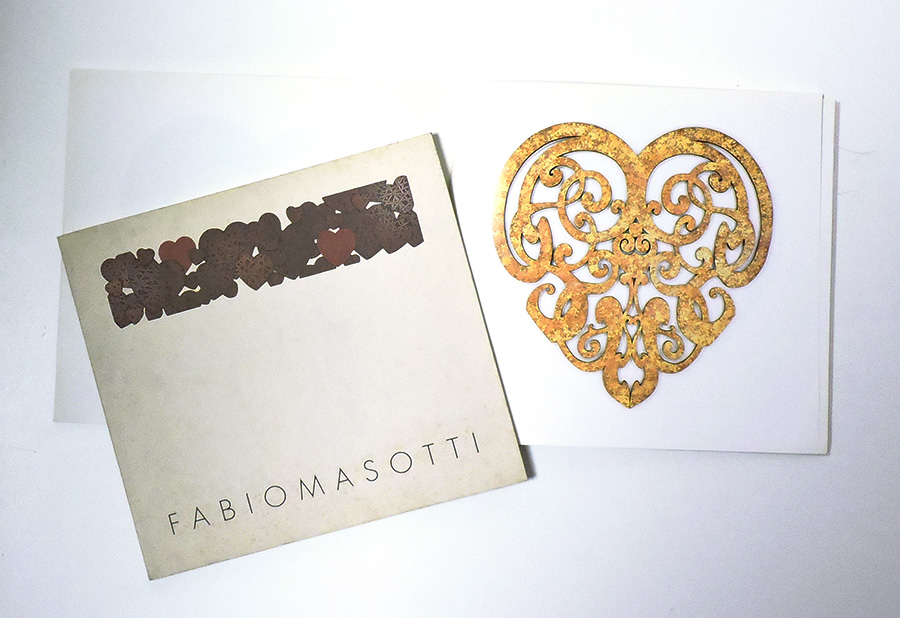

If using acrili paint arouses the surface of horizontal lines the thypographic vertical columns mime the beating of the pulsanting heart. The painted lines can be volumetrical background painting delineated by the cut line: the incision on the tarsia assembles plates and copper painted materials. The artist fundamentally opts for a Baroque or minimalist inlay, in a volumetrical stratification of materials which breaks down the qualification of surface. What remains of previous cuttings are reused in new collages. Either a bolted plate or cut up cloth mimes the ancient shroud. A ship’s rope, a tow-rope weaves around a body of the line which holds the boat/heart. Its entanglement of knots is a maze inlay: it is a journey blocked by the lack of harmony of the labyrinth. The inlay can also live alongside painting, in this way the heart acquires the dyptych story both forward and back, day and night. The inlay of a plate can become the naturalistic inlay of flowers squashed onto the surface and outlined and perforated in a geometric reduction of their own figuration. The coloured plaster and the acrili enamels form a black alchemist’s mirror through which, among Etruscan and obscure Bruges Liturgists, Masotti fills the mistery of the reflection inside the obscurity which has been scratched by informal striations, the footprints left by the reflected soul. Or we can see a heart with a halo of iron, nails which stick out into the void and go back to the cotton spider’s web which ties all the points of connection from nail to nail, from part to part: not a painted line nor an inlay but the physical body of a rope/line which weaves through the heart of passion, a true “Sacred Heart”.

So the inlay and weaving become a brocade embroidery and an Arabian inlaid embroidery. From the horror of the void an unrestrained eroticised linearism emerges which turning on itself fills the space, as if by paradox the void fills the void. The void is turned into a significant filled space when a topographic indication from a geographic map plays chessboard to the figure of the heart: the journey is the modulating of the chessboard to live both a victory and a defeca in the game of chess, the right to live, or the defeca of death: the knight who comes from the exotic geography of Jerusalem does not meet death, and only plays his last game with death, a game of chess, and he decides on how far to lenghten the season, and what we can have in return. To travel and lose oneself in the streets of the heart, i sto find oneself “out of breath”. Walking on a pilgrimage with one’s heart in one’s hand smiling in happiness at the conclusive meeting which makes walking itself a pilgrimage.

Travelling in Art for Masotti has been and continues to be a continual wonderment in finding materials and instruments to invent figures somewhere between abstraction and iconological representation of the image. Lidia Reghini from Pontremoli has already confirmed that Masotti succeeds in “assimilating and retransmitting the elements of the vision within a new synthesis which rather than through abstract figurative typology, will be espressed through the extension of a more global discussion of Art (…) Masotti’s work”, Reghini continues, “is understood not a single entity but rather as a continuing and tempting interaction of molecular parts”. These “molecular parts” have pervaded the complete cycle of works of his belve “Via Crucis”. Masotti enters through shards of images into the depths of the body reaching the centre of the temple, and if the body and temple is (male and female) the face of the picture, then the picture has a heart whose “centre” and “sign” of the body i salso the temple. One may conclude by remembering Reghini’s analysis which reads: “it is as if the artist wished to plot the traces o fan archaic form. These traces which is scado, is projected onto the moving surface of the picture, to then be violently overturned to the foreground, directly in front of the observer. This essential image of memory is what remains of the shattered unity that the artist strives to piece together not in terms of true likeness but in those of meaning”

Traduzione Paola Romagnolo

The expressive revolution that marked the first half of the twentieth century – the rupture of figuration into conceptualism and abstraction so enigmatic that it demanded to become essential – immediately emerges as the clear, unequivocal starting point of Fabio Masotti's artistic career. New materials, shapes and colours, some used monochromatically, others serving only to open up new paths for art, typified a period when everything had to be reconceived in terms of free expression far removed from the figuration of previous centuries. Not long afterwards, a need for a more accessible, more understandable language emerged, culminating in Pop Art’s transformation of the most popular symbols into the icons of a new art that was certain to conquer all.

Fabio Masotti’s art splendidly and unexpectedly synthesises these two starting points: the conceptual, with his careful research into materials; and the Pop. He chooses what is probably the most common sign in everyday culture, an icon that represents and has represented so much within the common imaginary: the heart. Fabio Masotti’s language is simple and direct, at least in its most external form. His chosen symbol has been reinterpreted and re-declined in a thousand ways yet, with a second, deeper look we see that it hides more profound, more philosophical, more universal notions to do with the essence of being human and of our journey through life. Masotti uses wood, metal, plaster, string and enamel to express the poetry and the intensity of bonds and emotions that go beyond the heart to reach the depths of the soul. At times, the visual impact of his works is so strong that it almost seems to scream of an overwhelming emotion. At other times, it is simply present, latently, silently describing how life and contemporary reality have shaped and sometimes hidden from us the essence, the original and purest meaning of life. The contamination of current life often distracts us from what is really important, from simplicity, naturalness and from the centrality of that substance which is, after all, the essence of life itself, and which is capable of crossing the barriers of time to remain indelible in our memory. Masotti uses his materials to forge and sculpt the concept, the message, the story through images that, every now and then, seek to express the discomfort of the contemporary world, the loss of values, the conformity to which emotion is often subjected, almost as if the loss of individuality has become a reassuring way to stay within boundaries that allow one not to be alone.

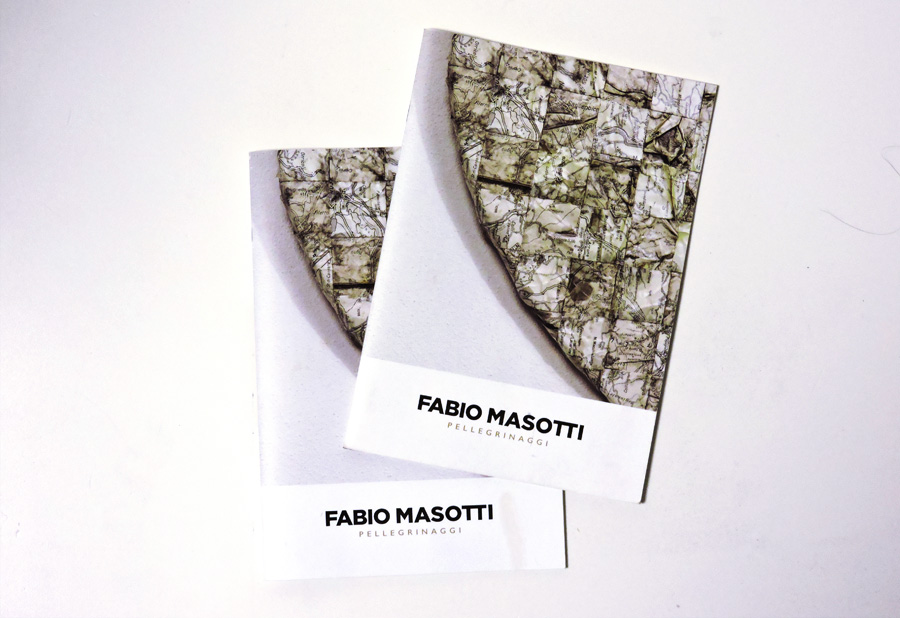

This is precisely the context in which the idea of the Pilgrimages exhibition unfolds. It is the notion of finding the courage, the soul’s inner strength linked to the heart, the concept of setting off on a journey, of embarking on an initially individual path on the search for a self that often requires solitude in order to later find a way and a desire to be amongst the multitude. After all, it is only discovering ourselves, our own depths, strengths and weaknesses that allows us to join with others who do not fear the path. Masotti uses street maps and wallpapers, cutting and decomposing them to then recompose them in the iconic shape of the heart framed in wood. For Masotti, the start and end points are less important than the movement itself, the evolution, the desire to learn all that there is to learn along the way, as well as the meetings with all those who accompany us on our journey.

The final chessboard composition emphasises how important it is to initiate an action, a movement that triggers a mechanism of cause and effect after which nothing will be as it was before that initial impulse, just as the now can never be the same as the after. The constant mutation and evolution of our essence, that perpetual movement, is sure to fundamentally enrich our understanding of ourselves in relation to others. Pilgrimages have always represented our need to get in touch with our inner selves, following the lead of religion to learn how to dig deep down into ourselves in search of answers that are often difficult to find without help, without a moral or emotional support. But it is precisely this emotionally engaging effort that helps us to discover within ourselves all the strength and answers we seek from the outside, even though our external aspect is fundamental in allowing us to reach this awareness. We recompose these maps of our own personalities which, without the previous fragmentation, the rupture of apparent and reassuring certainties, would never come to fruition.

Un simbolo intorno al quale Fabio Masotti riconduce la sua produzione artistica, dove la sagoma rappresenta sia l'elemento figurativo, sia la forma stessa dell'opera.

I lavori di Masotti, a metà strada tra quadri e sculture, pervengono a noi come sintesi di un concetto sviscerato e sviluppato all'infinito, dove la ricerca di materiali e sovrastrutture, di legni e metalli, conduce verso un sentiero inesplorato di combinazioni materiche, di volumi e profondità. Accurate composizioni dove il colore si fa forma dell'opera e ogni materiale assume la propria valenza espressiva.

Sono opere materiche che inizia a realizzare intorno agli anni '90, quando abbandona la pittura metafisica e surrealista per rispondere all’esigenza di dare forma alle sue idee, cercando altri mezzi espressivi.

L'intento principale è quello di stabilire un contatto diretto con lo spettatore.

L'esperienza tattile con le sue opere, infatti, permette di umanizzarle, e la scelta di una forma-simbolo come il “cuore” crea un rapporto di dialogo diretto con l'artista e con quello che vuole rappresentare. L'immagine simbolo della pop art, universalmente nota e riconosciuta, comprensibile a tutti, è il mezzo attraverso il quale Masotti veicola il suo messaggio, ciò che sente di dover rappresentare, che fa parte di un'indagine conoscitiva verso il mondo interiore e l'essenza dell'uomo. La parte più intima e spirituale, ma anche la sua forza e la sua vulnerabilità. Forse per questo le sue ultime opere, dove il legno zincato conferisce un aspetto ferroso seppur artificioso all'insieme composito, rimandano alla mente gli scudi medievali, o il meccanismo di una cassaforte impenetrabile.

I suoi lavori partono non più da un disegno ma da un'intuizione, molto spesso di carattere concettuale. Inducono a letture interpretative che vanno oltre la semplice sagoma ritagliata sul supporto: sono storie che si raccontano e trovano un senso compiuto tra le righe, le trame e gli ingranaggi, l'inserimento di catene e corde che rappresentano i legami, o i ritagli intrecciati di mappe stradali che indicano i pellegrinaggi del cuore e dell'anima. Il soggetto diventa una grafia, un misterioso pittogramma.

Dalle opere volumetriche di grande formato ecco che Masotti riduce le dimensioni fino a farle diventare un gioiello, piccole opere d'arte da indossare che diventano accessorio moda. E' normale per Masotti esprimersi in più linguaggi, perché gli è congeniale, è un artista che ama la manualità e la creatività oltre i limiti della forma. Grande cultore e collezionista di arredi del primo '900, anni in cui l'arte decorativa toccava l'apice dell'estetica nella forma del liberty e dell'art decò, Masotti ha saputo riportare nel suo lavoro di art-designer l'espressione artistica della decorazione intesa come gusto colto del bello. Nel corso degli anni ha concepito una forma nuova nella composizione del mobile d'arredo, contemporaneo e raffinato, pulito di ogni sovrastruttura e curato in ogni dettaglio. Un connubio di estetica e funzione che trova un punto di equilibrio nel suo personalissimo stile che conferisce alle sue creazioni un fascino di antica memoria.

I suoi mobili e complementi d'arredo sono oggetti curati, pensati e costruiti da mani sapienti, che si nutrono anche di quell'esperienza estetica del ‘900 che, come dichiara Masotti, ha sicuramente influenzato la sua formazione di art-designer, ma che poi ha superato pervenendo ad una sua personale e contemporanea sintesi espressiva.

Nell’ottica di un progetto che vede Masotti impegnato nel rendere la sua arte più diffusa ed accessibile, oltre le opere uniche, nascono nuove opere a tiratura limitata, realizzate con le più moderne tecnologie, che apriranno nuovi mercati ed attireranno nuovi, e magari più giovani, collezionisti.

There is no love, not even where the heart reaches. There is solidarity, however, pietas, sometimes a desire for missionary passion. Love is something else. It is in the psyche – which is only in love with its own destiny.

A drawn heart is a simple picture, too often absent from geometry books. It is a picture found in universal language. It the sign of every time, cut into the bark of trees or sketched in schoolchildren’s exercise books. It is the symbol of every love, pierced as it is by Cupid’s arrow, bleeeding.

Even cities have hearts. Like men. And they breathe that same air which they produce.

The vital organ of a city is a heart which beats to the rhythm of its traffic lights, its underground trains, its businesses.

But the heart men carry within them lives on emotions, dreams, rushes of sentiment, desires. It lives on humanity.

The heart of man is the nucleus of his feelings, but also of his secrets. Its antagonist is the mind, which means rationality. While the heart is all passion, impetus.

Yeti t is often the heart which leads the way, decides what is to be done, what to choose. And the affairs of the heart are inextricable.

That is why the heart is the best part of man; it is the part which intervenes where there is a cry for help, where a desire goes unfulfilled, where there is a need for solidarity. Where a love is born. It is only then that man’s love takes the form of the heart.

And yet, however great they are, the single hearts of men are insufficient in the great labour of humanity. The heart of the cities is also necessary. And above all it is necessary that the poetry of art matches up to the cynicism of technology. This is why artists can express the heart’s reasons better than anyone else and above all enable everyone to understand them. In that universal language which is art.